Where's the Horizon?

The horizon was John Ford’s signature.

“How would you like to meet the greatest director who ever lived? And he’s right across the hall.”

The young man’s on his first day at a new job at a TV studio, and he wants to be a filmmaker.

He follows his boss to the office across the hall.

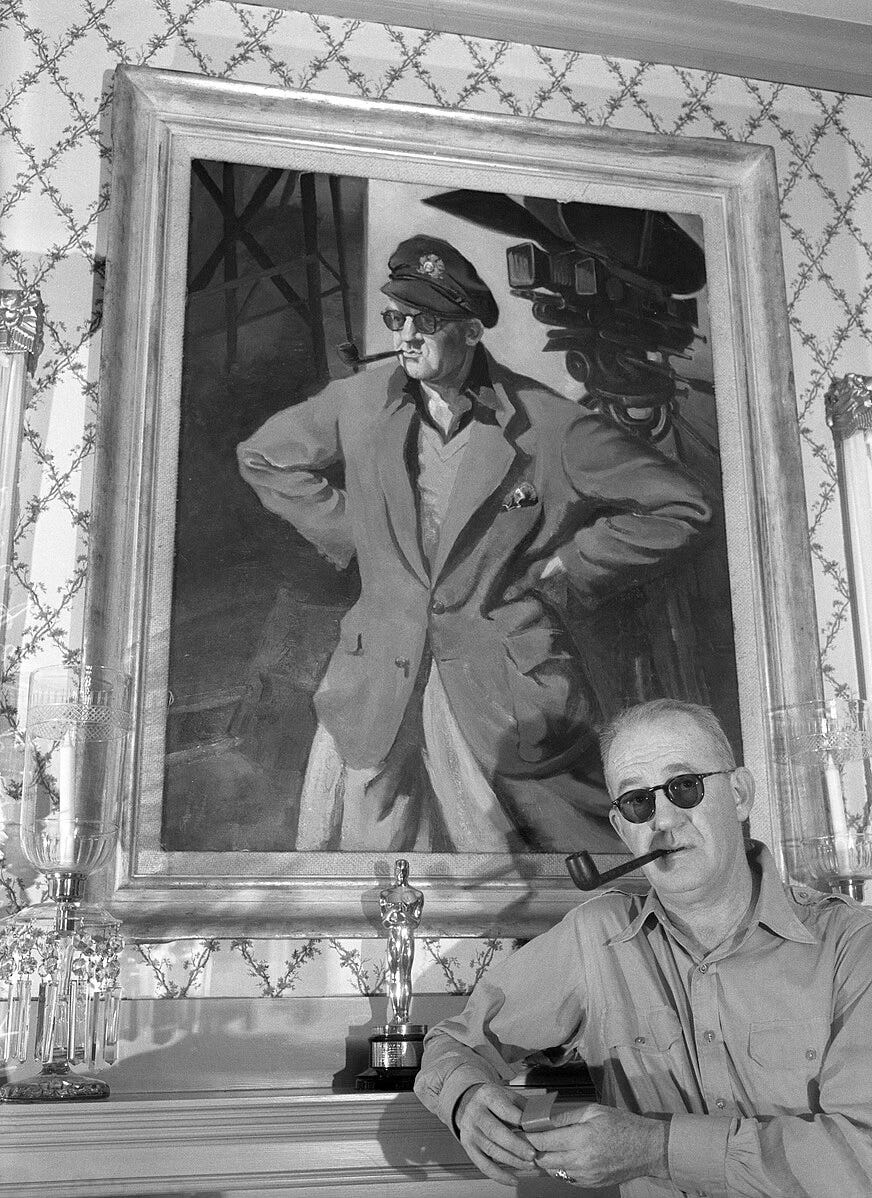

His boss leaves him alone with “the greatest director who ever lived.” The director lights a cigar and tells the young man to look at a painting on his wall and then another and another. Every time, the director, John Ford, asks the young man: “Where’s the horizon?”

The horizon was Ford’s signature. “When the horizon’s at the top, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s at the bottom, it’s interesting. When the horizon’s in the middle, it’s as boring as shit,” he told the young man. (The young man listened and did become a filmmaker). In Ford’s first big success Stagecoach, the horizon, that flat line that marks the border between the hot, dusty and jagged Arizona plains and the clear sky, goes up and down from the top to bottom as scenes and days break in the multi-day trek the characters make across Arizona in an overland stagecoach. It changes inside a single shot too. The stagecoach is galloping across the dessert that’s empty of hostile Apache. It’s far from the camera. The stagecoach is a faraway dot being gradually and easily pulled along the serene landscape. Ford swerves the camera left and shows the Apache war party massed on the cliffs overlooking the plain the stagecoach is crossing, their guns raised, ready to attack, their sheer number filling almost the entire mid-section of the shot. With that one pan, Ford drops the horizon from the top to the bottom. Although it looks a lot like it’s in the middle, it’s still closer to the bottom than the top. There’s not an equal amount of space above and below the horizon.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Into the Screen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.